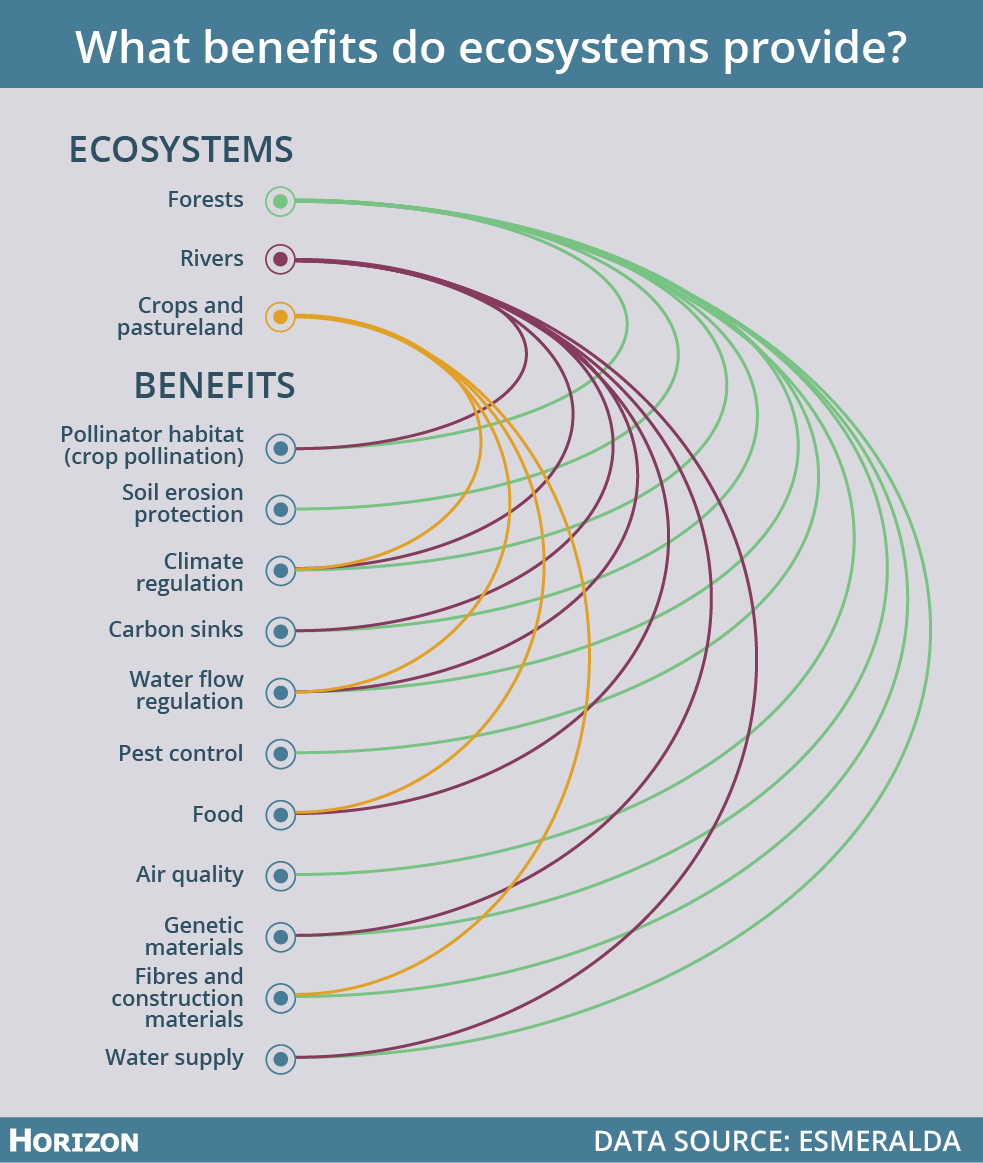

The concept of quantifying these so-called ecosystem services, which has grown in recent years, has proved controversial for some environmentalists who oppose reducing nature to numbers. Others see it as a way to get businesses and policymakers to account for nature to make better decisions that preserve biodiversity.

First, though, working out what ecosystem services we have, and how much of them, requires mapping where they are. To aid this process, a project called ESMERALDA tested tools and methods to help decision-makers map and assess ecosystem services across Europe.

The end result is an open access online tool that provides full guidance for mapping and assessing ecosystem services.

‘The key message is to show the human dependence on functioning nature. Everything that we get and receive is related to ecosystems and their functions, and biodiversity,’ said Professor Benjamin Burkhard, a geographer at Leibniz University in Hannover, Germany, and project coordinator of ESMERALDA.

‘If we can really show how much a tree, for example, provides us with fresh air or how much carbon it’s sequestering, I think we will have more appreciation of nature’s contribution in society and decision-making,’ he said.

Land use

ESMERALDA’s approach takes into account three areas – biophysical, which refers to physical factors such as land use or volume of greenhouse gases – sociocultural and economic.

In its country case studies, ESMERALDA assessed different ways of valuing the three areas. For example, a study on Germany’s Bornhöved Lakes District combined biophysical data such as crop volumes and numbers of pollinators with sociocultural information including a survey of people on the aesthetic values of landscapes.

Prof. Burkhard says that a wide-ranging assessment is important to obtain a full picture. ‘It doesn’t help you to only have an economic value, but it also doesn’t help you to only have a social value. You need to have the whole set of biophysical, social and economic values for a perfect assessment,’ he said.

‘I’m an ecologist and would be happier if people were convinced just by having nice nature and lots of species – but this is not the way the world works at the moment, and usually the most convincing argument is money.’

Prof. Benjamin Burkhard, geographer, Leibniz University, Hannover, Germany

On the thorny issue of attaching economic values to nature, he says this approach can help raise awareness among policymakers and businesses.

‘I think it’s at least a good tool to convince many people,’ he said. ‘I’m an ecologist and would be happier if people were convinced just by having nice nature and lots of species – but this is not the way the world works at the moment and usually the most convincing argument is money.’

Prof. Burkhard says that awareness among EU decision makers about ecosystem services has grown over the course of the three-and-a-half-year project, which ended last July. The next stage for upcoming projects will be to start applying the ESMERALDA methodology in real-life situations, such as policymaking at a national level on issues such as agriculture, or local spatial planning.

For Guy Duke at the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW) valuing the world’s natural capital – its stock of natural assets – could help businesses make more environmentally sustainable decisions. However, he says that we are only at the ‘tip of the iceberg’ in terms of the number of companies that have started to understand and address this. ‘There’s a very long way to go,’ he said.

Duke leads the We Value Nature campaign which seeks to encourage businesses to embed the value of nature into their decision-making and apply the Natural Capital Protocol. This is a global set of standards that allows businesses to identify, measure and value what role natural capital plays in their business. The project is run by ICAEW, and other organisations that are part of the international collaboration, the Natural Capital Coalition.

Catalyst

‘We see our role very much as a catalyst of this idea,’ said Duke. ‘There has been a sea change in recent years, with the whole paradigm of natural capital finding its way into the policy space and business.’

Since launching last November, the project has started reviewing barriers and bottlenecks that impede businesses from investing in natural capital, with training to be later developed for companies.

Duke says one aim is to identify industry sectors in which action will bring the most benefit to nature, followed by specific businesses in those sectors and then individuals with the most influence on shaping decisions that affect natural capital and biodiversity.

Richard Spencer, head of sustainability at ICAEW, believes the approach is necessary. ‘To get business to grasp the quite perilous position we’re getting to, you’ve got to couch it in terms that people such as finance directors understand,’ he said. ‘If it’s economically invisible, people don’t make decisions about it.’

Spencer says some companies have recognised, for example, that restoring wetlands acts as an effective flood defence, thus saving money.

Nature

Spencer stresses that the project is not about attaching a single price that commoditises nature but about ascribing a value through a mix of descriptive information and numbers to build a complete story. ‘We never, ever put a price on nature,’ he said.

Natural capital is, however, far from an easy bedfellow of biodiversity and the term has provoked fierce debate among environmental activists such as the British campaigner George Monbiot who argue that the concept is not only wrong, but counterproductive.

Dr Berta Martín-López, a professor for sustainability science at the Leuphana University of Lüneburg, Germany, who worked on an earlier ecosystem services project called OpenNESS, warns future biodiversity programmes against putting too much stock in monetary value as a whole.

‘To me, the homogenisation of world views to only one simplistic view that fits with the mindset of monetary values and capitalism is the most dangerous pressure for biodiversity,’ she said.

‘By expressing values of nature only in monetary terms, we are not only overlooking the plural ways by which people give importance to nature, but also neglect multiple actors’ voices and their needs and interests.’

Dr Martín-López highlighted that nature goes far beyond just providing basic services – it also offers intangible, non-material benefits that cannot be valued in monetary terms.

‘The multiple ways by which people develop relationships with nature contribute to the construction of our cultural identity, sense of place and belonging,’ she said.

The approaches that will pave the way for the future, she says, are those that ‘foster a diversity of world views’.

The research in this article was funded by the EU. If you liked this article, please consider sharing it on social media.

This post The business of biodiversity: can we put a value on nature? was originally published on Horizon: the EU Research & Innovation magazine | European Commission.

Print this article

Print this article